My Barracuda “Backup Server 290” Journey

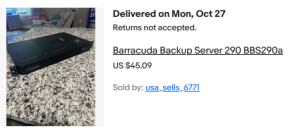

Back in October of last year, I got bit hard by the eBay bug. “Woah, that’s actually a pretty reasonable price… I’ll do SOMETHING with it!” — and just like that, I became the owner of a lightly used Barracuda “Backup Server 290.”

What is the BBS290, one might ask? Essentially, it’s a 1U rack-mount backup appliance. This one was running CentOS 7 with some custom interface stuff at both the VGA console as well as on a web server running on the box — basically a proprietary backup solution built from open-source software and a mix of consumer PC hardware, with some enterprise bits included.

I got mine for $40 USD, with the unusually low shipping price of $5. Shipping is usually the killer on these things; expect any 1U server to be listed with a shipping cost between $30 and $100.

What $45 Got Me

Honestly, not a bad little backup server. Funnily enough, that is exactly what I’m going to use it for: a target to back up my main server to.

As it arrived, it included:

• 1U Mini-ITX rackmount chassis

• 1U ATX power supply rated @ 400W, 80+ Bronze

• Western Digital enterprise-grade 2 TB 7,200 RPM SATA hard drive (Mfg 2022)

• Celeron N3150 on an OEM variant of the MSI N3150I ECO

• 1× 8GB DDR3 memory module

Not winning the lottery here, but with a few upgrades, this machine can fill a very real need in my setup. For this tier of hardware, I would not recommend paying more than $60–$70 total at the very most. That is up to you though. The platform (CPU, DDR3) isn’t worth a whole lot, and performance is underwhelming at best… but it is sufficient for what I wanted to do.

Low power draw, low heat, and the case and power supply are probably the best part of the “deal.”

The lightly used 2TB enterprise-grade drive was a nice bonus if you’ll actually use it for something. For instance, if 2TB was enough for your backup needs, then this box as-is is an excellent value. Most of us will want a bit more storage though.

Upgrades

- WD 8TB Enterprise Drive

Replaced the original 2TB HDD. This is a CMR drive, 7,200 RPM — not SMR or 5,400 RPM (two big gotchas to look out for). I shucked it from an 8TB WD MyBook purchased locally for $150; it had only ~600 power-on hours. Shucking is far from foolproof, but I got very lucky to get a top-tier hard drive that had barely been used. It will live much longer being used in this server than in the fanless plastic heat trap it came in as a MyBook.

- G.Skill 8GB DDR3L RAM ×2 (16GB total)

Helps with ZFS caching. Cost: $16.86. A basic setup could run with 8GB, but doubling helps ZFS performance. Additionally, using two memory modules allows the memory controller to operate in dual-channel mode, effectively doubling memory bandwidth. On an anemic CPU like the N3150, this can make a surprisingly substantial difference for I/O, especially when ZFS is handling many small files or metadata-heavy operations.

- Intel 480GB SATA SSD

Data center–grade SSD costing about $25 on eBay. It allows the OS and root filesystem to live off the spinning disk and can also be used to accelerate ZFS performance via a special vdev for small file storage. You don’t need to do this if your data is mostly large files, media, or ISOs — but for small files, the performance boost is noticeable. If the special vdev disk dies, the pool dies — which is acceptable here, because this machine is strictly a backup target.

- Intel i226-V 2.5GbE NIC

Cost: $30, combined with a PCIe x1 ribbon riser ($8.59) and some DIY shielding. This upgrade doubles network throughput over the onboard 1GbE Realtek NIC for very little money. Drivers are mature and stable on both BSD and Linux. For nighttime backups or casual use, the onboard NIC is fine; this is a small cost for a large convenience.

Total upgrade costs:

• RAM: $16.86

• SSD: $25

• NIC: $30

• PCIe riser: $8.59

• 8TB WD CMR HDD: $150

Grand total: $230.45 (including the original $45 for the machine itself)

Chassis and Cooling

The chassis originally had a lit Barracuda Networks logo and a cheap internal 40mm fan. I removed both and resprayed the case dark red for a fresher feel. The stock fan was noisy, and the PSU provides sufficient airflow, so I skipped adding a replacement.

I’ll keep an eye on temperatures. The CPU doesn’t require a fan at all. The 7,200 RPM disk gets slightly toasty, but it’s far better off here with airflow than in a MyBook enclosure with none.

OS Choice

I mostly run Linux, but I appreciate the technical merits of FreeBSD, especially for enterprise-grade storage and high-performance, low-latency applications. On FreeBSD, ZFS is a first-class citizen, unlike Linux where it’s often bolted on.

I initially experimented with XigmaNAS but wanted more control, so I went with FreeBSD 15.0-RELEASE.

Honestly, if you want to keep things simple, just go for XigmaNAS or TrueNAS Core. Both are solid FreeBSD-based storage appliance OSes which make ZFS much more approachable. Linux ZFS implementations like Ubuntu’s are fine, but FreeBSD is where it truly shines.

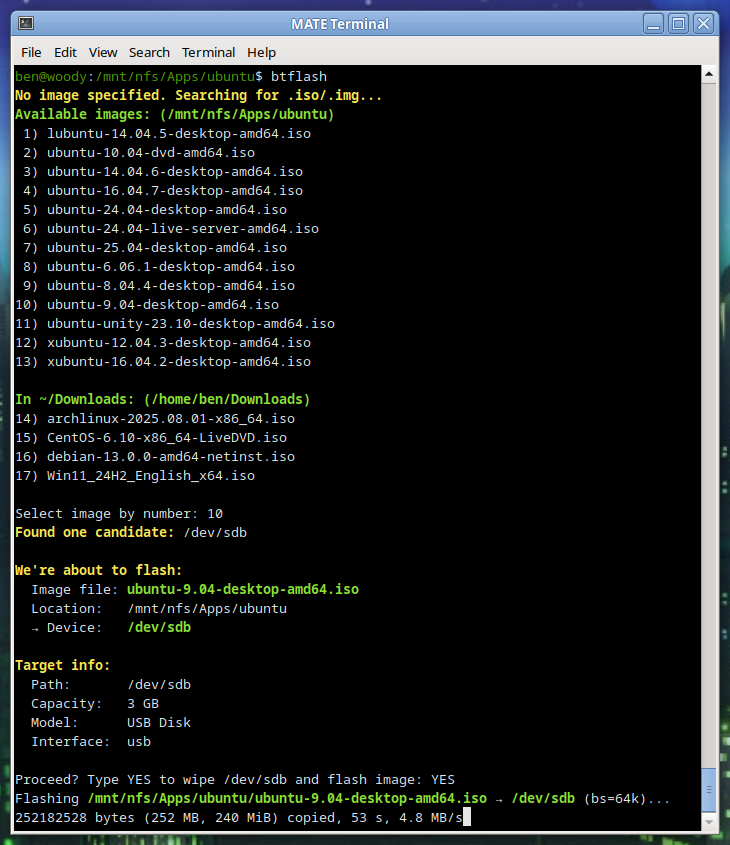

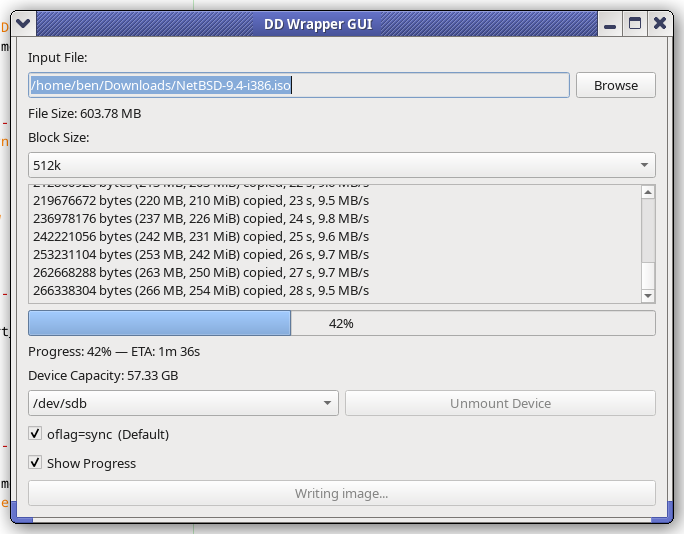

Installation

I wrote the 15.0-RELEASE image to a USB stick and booted it. Setup asks whether to install via Distribution Sets or Packages (Tech Preview); I used Distribution Sets.

• Disabled kernel debugging and lib32 support

• Selected the igc0 NIC (leaving re0 unused)

• Chose manual partitioning:

– 480GB SSD: MBR, 64GB partition for root / (UFS), SUJ off, TRIM on

– Swap: 2GB partition as freebsd-swap

– Remaining HDD space left unpartitioned for ZFS setup post-install

Enabled SSHD, NTPD, and powerd. Added a user in the wheel group. Other options left at defaults.

Post-Installation Storage Configuration

Check free space on the SSD:

gpart show ada0

This revealed ~383GB free for the ZFS special vdev:

gpart add -t freebsd -s 383G -a 4k

ada0

gpart create -s BSD ada0s2

Create the main pool on the 8TB HDD:

zpool create -f tank /dev/ada1

Add the special vdev on the SSD for small files:

zpool add tank special /dev/ada0s2

zfs set special_small_blocks=128K tank

Set mountpoint and ownership:

zfs set mountpoint=/mnt/tank tank

chown -R 1000:1000 /mnt/tank

Enabling and Setting Up NFS

Enable ZFS and NFS-related services:

sysrc zfs_enable="YES"

sysrc rpcbind_enable="YES"

sysrc nfs_server_enable="YES"

sysrc mountd_enable="YES"

sysrc rpc_lockd_enable="YES"

sysrc rpc_statd_enable="YES"

The zfs_enable=YES setting is important: without it, ZFS pools may not automatically import and mount at boot. This was the reason the pool initially failed to remount after a reboot.

Start services manually:

service rpcbind start

service mountd start

service nfsd start

Edit /etc/exports:

/mnt/tank -network 10.16.16.0 -mask

255.255.254.0 -alldirs -maproot=1000:1000

• -network / -mask restricts access to your LAN

• -alldirs allows mounting subdirectories

• -maproot=1000:1000 maps all remote users to a local UID/GID

Apply the configuration:

service mountd restart

service nfsd restart

This method alone works reliably. Using zfs

set sharenfs is unnecessary here and can introduce confusion.

Syncing Data via NFS

Mount the NFS share on the main server at /mnt/cuda, then ensure permissions:

chown -R 1000:1000 /mnt/tank

chmod -R 755 /mnt/tank

Run rsync:

rsync -avh --info=progress2 --modify-window=1 /mnt/sda1/ /mnt/cuda/

• -a preserves timestamps, permissions, symlinks, etc.

• --info=progress2 shows real-time progress

• --modify-window=1 handles timestamp differences between Linux and FreeBSD

Observations:

• The SSD-backed special vdev noticeably improved small-file performance

• Dual-channel memory helped I/O on this low-power CPU

• The 2.5GbE NIC provides a large convenience boost

• Transfer speeds are currently limited by the source system’s storage and workload characteristics

Real-World Testing

Copying a 4.1GB Debian ISO from the Barracuda to my desktop completed in roughly 10 seconds. Both machines and the switch are 2.5GbE capable. Renaming the file and pushing it back (desktop → Barracuda) took about 15 seconds.

Htop reported 100–200 MB/s in both cases, though reads from the Barracuda are clearly faster than writes.

Pings between the two machines show excellent latency and consistency:

100 packets transmitted, 100 received, 0% packet loss

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.103/0.114/0.175/0.009 ms

Closing Thoughts

For now, all my personal goals for this project have been met. Eventually, I plan to implement scheduled wake-on-LAN (or something conceptually similar) so the box only powers on when backups are needed. I don’t need it running 24/7 — it’s here to quietly snag incremental backups in case something goes wrong elsewhere.

For those new to FreeBSD, maintenance is fairly simple. Updates are handled with freebsd-update fetch install. After fetching, you’ll see a wall of text — press q, and the install will proceed.

That’s all for now.

FreeBSD 15.0: Notable Improvements for Desktop and Laptop Users

FreeBSD 15.0: Notable Improvements for Desktop and Laptop Users